5005 S. Cooper St.

Suite 250

Arlington, TX 76017

A Cancer Diagnosis Is Scary

No one wants to hear, “You have bladder cancer.” But here’s the good news: Detected early, bladder cancer is very treatable. Unfortunately, there is no early screening test for bladder cancer. Most people are diagnosed after they notice blood in their urine. When facing a diagnosis of bladder cancer, it’s important to seek the expertise of experienced bladder cancer doctors for the best possible care and treatment options.

At Urology Partners of North Texas, our top bladder cancer doctors & specialists help men and women understand their bladder cancer and all their treatment options.

We Are Warriors!

Every day we go to-to-toe with urologic cancers. Our passionate, patient-centric approach pushes us to find better ways to eradicate bladder tumors. We’re equally committed to pairing the right bladder cancer specialists with each individual who comes to us—a skilled fighter uniquely qualified to deliver truly personalized care.

What is bladder cancer?

Not all bladder cancer is the same.

Urothelial carcinoma (also known as transitional cell carcinoma) is the most common type of bladder cancer. This cancer starts in the urothelial cells that line the inside of the bladder. Cancerous cells may also spread to other parts of the urinary tract that contain urothelial cells in their lining, including part of the kidneys, the ureters and urethra.

Squamous cell carcinoma makes up about one to two percent of all bladder cancers, but are almost always an invasive form of the disease.

Adenocarcinoma is a highly invasive form of bladder cancer that is only about one percent of all bladder cancers. These cancer cells have a lot in common with colon cancers.

Small cell carcinoma is extremely rare and makes up less than one percent of bladder cancers. They form in nerve-like cells called neuroendocrine cells and usually grow quickly.

Sarcoma cells form in the muscle cells of the bladder and are very rare.

What causes bladder cancer?

Researchers are still not certain what causes bladder cancer, but there are several risk factors that can trigger the disease. Some of these risk factors—race, ethnicity, age, gender, family history or congenital birth defects—cannot be controlled. Caucasians, men, people over 55, people born with rare bladder birth defects and individuals with a family history of bladder cancer are at greater risk.

Still, there are many risk factors associated with bladder cancer that individuals can control.

- Smoking causes about half of all bladder cancers in men and women. Smokers are nearly three times more likely to be diagnosed with the disease than non-smokers.

- Exposure to industrial chemicals often used to make rubber, leather, textiles, paint and printing products increases the risk for bladder cancer.

- Certain medicines and herbal supplements including the diabetes medication pioglitazone (Actos) and dietary supplements containing aristolochic acid have been linked to an increased risk of urothelial cancers.

- Arsenic in drinking water boosts an individual’s risk of bladder cancer.

- Fluid consumption is linked to bladder cancer. People who drink a lot of fluids (especially water) have lower rates of bladder cancer. Emptying the bladder more often helps flush toxic chemicals from the bladder.

Diagnosing bladder cancer.

Bladder cancer is diagnosed using a variety of tools.

A medical history and physical exam assess overall general health and any risk factors. Sometimes, a bladder tumor can be felt during a physical exam.

Urinalysis checks for blood and other substances in a sample of urine.

Urine cytology looks for the presence of cancer and pre-cancer cells using a microscope.

Urine cultures determine if a bacterial infection might be causing symptoms rather than cancer.

Urine tumor marker tests confirm the presence of bladder cancer. One or more tests may be used, including NMP22 (also known as BladderChek), BTA Stat, Immunocyt and UroVysion.

Cystoscopy offers a view inside the bladder via a long, thin tube with a light and a lens or a small video camera on the end. A fluorescence cystoscopy (blue light cystoscopy) may be done along with routine cystoscopy to fill the bladder with a light-activated drug that is absorbed by cancer cells. When the physician shines a blue light through the cystoscope, cancer cells will glow—allowing abnormal areas of the bladder to be visible.

Transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) collects biopsy samples of abnormal-looking bladder tissue spotted during a cystoscopy. This tissue is sent to a lab to be examined by a pathologist. During the procedure, the physician removes the tumor and some of the bladder muscle around the tumor. Samples from several different parts of the bladder may be collected, especially if cancer is suspected but a tumor isn’t visible.

Biopsy confirms the presence or absence of bladder cancer. If cancer is detected, the pathologist indicates whether it is non-invasive or invasive and determines the cancer’s grade. Non-invasive cancer is confined to the inner layers of cells. Invasive cancer has spread to the deeper layers of the bladder. Grade is assigned based on how the cancer cells look under a microscope.

- Low-grade cancers look more like normal bladder tissue. People with these cancers usually have a good prognosis.

- High-grade cancers look less like normal tissue. High-grade cancers are more likely to grow into the bladder wall and spread outside the bladder. These cancers can be harder to treat.

Imaging tests such as x-rays, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), sound waves (ultrasound) and tests that use radioactive substances to create pictures of the inside of the body may all be used to determine if the cancer has spread to tissues and organs near the bladder, nearby lymph nodes or distant parts of the body

Staging bladder cancer.

After studying biopsy samples of the bladder tumor under a microscope, a pathologist determines the grade and stage of the tumor. Staging reveals how much of the tissue contains cancer. The stages of bladder cancer include:

T0 – there is no evidence of a primary tumor in the bladder

Ta – tumor is contained in the bladder lining and is not found in any layers of the bladder

Tis – carcinoma in situ (CIS) is a high-grade, but “flat” cancer

T1 – the tumor has invaded the bladder lining, into the second layer, but has not reached the muscle layer

T2 – the tumor extends into the muscle layer of the bladder

T3 – the tumor extends beyond the muscle layer and into tissue surrounding the bladder—usually fat surrounding the bladder

T4 – the tumor has spread to other areas near the bladder such as the prostate in men or vagina in women

Health Navigator

- Harrison “Mitch” Abrahams, MD

- Jeffrey Charles Applewhite, MD

- Jerry Barker, MD, DABR, FACR

- Paul Benson, MD

- Richard Bevan-Thomas, MD

- Keith D. Bloom, MD

- Tracy Cannon-Smith, MD, FMS

- Paul Chan, MD

- Kara Choate, MD

- Lira Chowdhury, DO, FACOS

- Weber Chuang, MD

- Adam Cole, MD, FS

- M. Patrick Collini, MD

- Zachary Compton, MD

- Adam Hollander, MD

- Patrick A. Huddleston, MD

- Justin Tabor Lee, MD

- Wendy Leng, MD, FPMRS

- Alexander Mackay, MD

- Tony Mammen, MD

- F.H. “Trey” Moore, MD

- Geofrey Nuss, MD

- Christoper Pace, MD

- Jason Poteet, MD

- Andrew Y. Sun, MD

- Scott Thurman, MD

- James Clifton Vestal, MD, FACS

- Keith Waguespack, MD

- Diane C. West, MD

- Keith Xavier, MD, FPMRS

Related News & Information

Life After the Lift (UroLift) is Great!

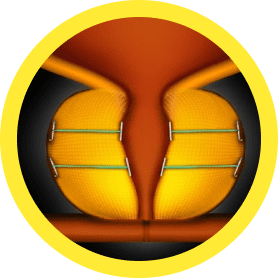

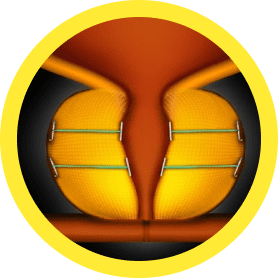

For many men, an enlarged prostate can make life miserable. The urgent need to go, urinating more frequently than normal, a weak urinary stream, difficulty starting and stopping—they’re all symptoms of BPH. Find out how the UroLift is helping men get their life back.

Treatment Depends on Several Factors

The grade and stage of cancer, risk factors, likelihood for recurrence or progression, and the individual’s age and general health are all considered when determining which treatment option is best.

Cystoscopic Tumor Resection

Intravesical Immunotherapy

Intravesical Chemotherapy

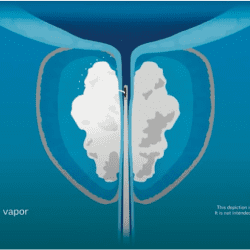

Intravesical chemotherapy is recommended for patients with low- and intermediate-risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). It is usually administered immediately or soon after a cystoscopic tumor resection, and has been shown to reduce the recurrence of NMIBC.

Under anesthesia, a catheter is inserted into the bladder through the urethra to deliver the appropriate chemotherapy drug. The drug remains in the bladder for an hour or two, then is passed out of the body through normal voiding. Patients usually go home the same day.

Cystectomy

Surgical removal of all or part of the bladder (cystectomy) may be recommended for patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer who do not respond well to other treatment.

- Partial cystectomy is a good choice if the tumor is located in a specific part of the bladder and does not involve more than one area of the bladder. The surgeon removes only the tumor and nearby lymph nodes.

- Radical cystectomy is usually performed when other therapies fail. The surgeon removes the entire bladder, nearby lymph nodes and part of the urethra. In men, the prostate may be removed as well. In women, the uterus, ovaries, fallopian tubes and part of the vagina may also be removed.

Individuals who undergo radical cystectomy will also need to undergo a urinary diversion—a procedure to address urine storage and elimination once the bladder has been removed. Options include:

- Ileal conduit: A piece of the patient’s upper intestine is used to create an opening on the surface of the abdomen. The ureters are connected so urine leaves the body through the opening. A bag is attached to collect the urine, and individuals empty the bag several times a day.

- Continent cutaneous reservoir: A pouch is created inside the body and patients learn to use a catheter to remove the urine.

- Orthotopic neobladder: An internal pouch similar to a bladder is created to store urine. The ureters are connected to the new “bladder” so individuals can empty it through the urethra the same way prior to surgery. In some instances, a catheter may be needed to remove the urine.

We Are Your Bladder Cancer Experts

Call for an Appointment

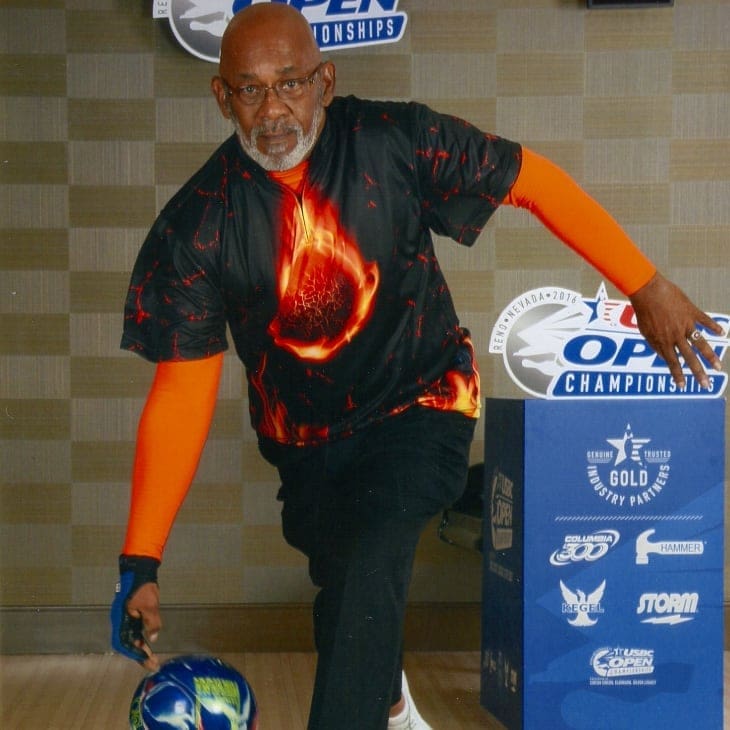

Two-Time Kidney Cancer Survivor Donald Kyle’s Message to African-American Men

Don Kyle’s father was just 56 when he died from cancer. He thinks about that—a lot. “As an African-American male, I know that my father had a reluctance to go to doctors,” Kyle says. “I don’t know why, our family had good healthcare. I know it’s something that is endemic